I’m used to seeing Fall Webworms at Blue Jay Barrens, but they have always been on trees or shrubs. There don’t seem to be many tree species that they won’t eat, so I guess it’s not unlikely that there are many plants they would find palatable. If that’s where the female laid her eggs, the larvae really don’t have much choice other than eat or die.

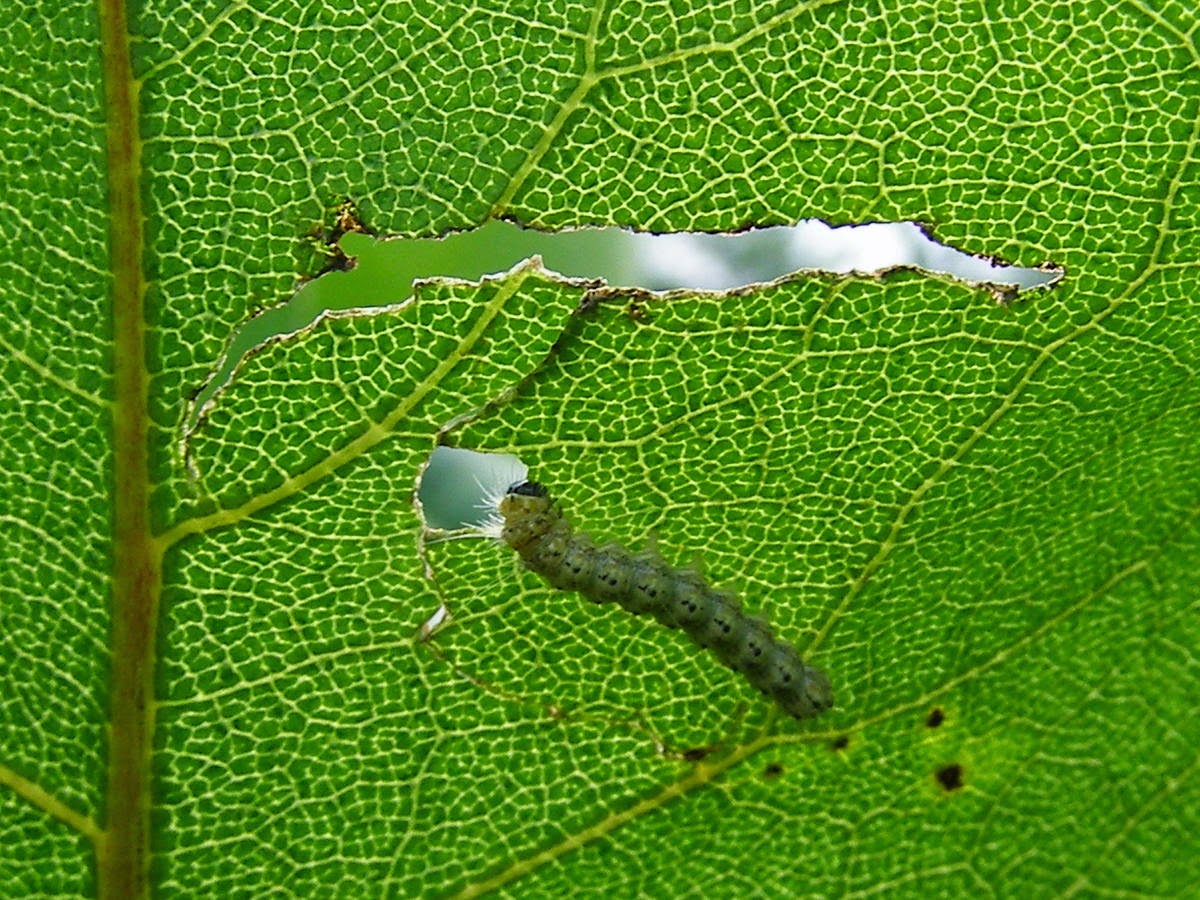

Fall Webworms are communal feeders that build a network of webbing that covers their feeding area. New silk strands have been stretched over the midrib of the dock leaf to offer protection to those caterpillars heading out to begin feeding on a new section of leaf.

I think this is the webworm equivalent of painting yourself into a corner. It won’t take long to eat this small edge piece. Then it will be a long trek to the other side of the leaf to find some more green.

As the name suggests, Fall Webworms are normally encountered towards the end of summer. In

Several of the webworms didn’t remain within the community. Bunching together is supposed to afford some measure of protection from predators. Maybe predators are more attracted to the mass of potential prey items and fail to recognize these lone individuals.

When I checked back a couple of days later, the webworms were gone. I looked around, but couldn’t find them anywhere nearby.

All they left behind were shed skins and frass caught in the old webbing. Fall Webworms typically leave the webs and go to the ground to pupate, but I wouldn’t think they would do that immediately after casting off their old skins.

The following day I found several individual webworms. These were all the next size up, a little larger and hairier than what I had seen on the Prairie Dock. Some were on the ground and others were munching on various plant leaves. Perhaps there is some type of dispersal that takes place prior to pupation, so the pupae aren’t all confined to the same small area. I’ll have to pay attention when more of these guys show up later in the summer. Maybe I’ll learn whether or not this is typical behavior for the species.